Shedding Light on Dark Energy

Dark energy and the nature of the universe are two of the most exciting discoveries of the past couple decades, but can be some of the most difficult concepts for non-physicists to grasp. More often than not, dark energy is just a futuristic-sounding prop in a science fiction novel. But while it may make for a fantastical plot tool, the real discoveries in dark energy are even more exciting. I’m going to do my best to explain a bit of the history of dark energy and some of the experimental evidence that helps to constrain the theory.

The History of Dark Energy

The original concept of dark energy was proposed by Einstein in his field equations in the 1910s, which essentially describe the behavior of matter due to gravity. A good analogy for Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity is a linen sheet, stretched tight – this represents the universe. Let’s scatter a few marbles across the sheet. Each will create a small dimple in the sheet. These represent mass in the universe – galaxies. Now we can observe the effect of gravity: each marble is going to start to roll towards nearby marbles due to each other’s dimples, as gravity causes massive bodies to attract to each other. This is the problem Einstein encountered: the universe couldn’t remain the same size if gravity were the only force to act on massive objects. To keep the size of the universe static, Einstein needed a repulsive force to counteract gravity, and essentially added a “fudge factor” to his field equations, which he called the “cosmological constant.” This constant would be a property of space itself.

When Hubble discovered that the universe was expanding in 1928, Einstein quickly abandoned the idea of a cosmological constant, purportedly calling it his “greatest blunder.” An expanding universe is no longer static, and therefore Einstein didn’t need a force to counteract the contraction due to gravity. Essentially, the expansion of the universe wouldn’t contradict his theory, provided that the expansion was slowing from gravitational pull.

However, in 1998, it was discovered that the expansion of the universe was accelerating. This no longer agreed with a model that only included gravity – the cosmological constant would have to be reintroduced. This accelerating expansion is the first piece of modern evidence that points towards the existence of dark energy.

Type Ia Supernovae

In 1998, Type Ia supernovae provided the first indication of the accelerating expansion of the universe. The explosions of these particular supernovae occur consistently enough that they can be used as a basis for a brightness measurement, referred to as a “standard candle.” Astronomers measure the amount of light received from a particular supernova, and, by tracking the supernova over several days, can estimate how much light the supernova emits at its source. This provides a measurement of how far away the supernova is. Then, by looking at the colors the supernova emits, astronomers can determine how quickly the star is moving away from Earth, using the Doppler shift, or “redshift” (the change in frequency as a result of velocity). Since it takes time for light from these supernovae to reach Earth, light from more distant supernovae was emitted longer ago, and similarly, light from closer supernovae was emitted more recently. Distant supernovae can thus give a measure of the expansion of the universe via their redshifts, and this is where the accelerating expansion was observed: closer supernovae are receding far faster than distant supernovae.

The model of the universe mentioned earlier dictates that there are four parameters that govern cosmology: matter (or mass), the radiation (or light), the cosmological constant (or dark energy), and curvature (or the shape of the universe). We can think of these as “fractions” of what make up the universe, as they add up to 1. (However, the curvature can be positive or negative.) So, if we don’t know anything about dark energy, we should still be able to make measurements of the other parameters and figure out whether or not the dark energy fraction is zero, i.e. if it actually exists.

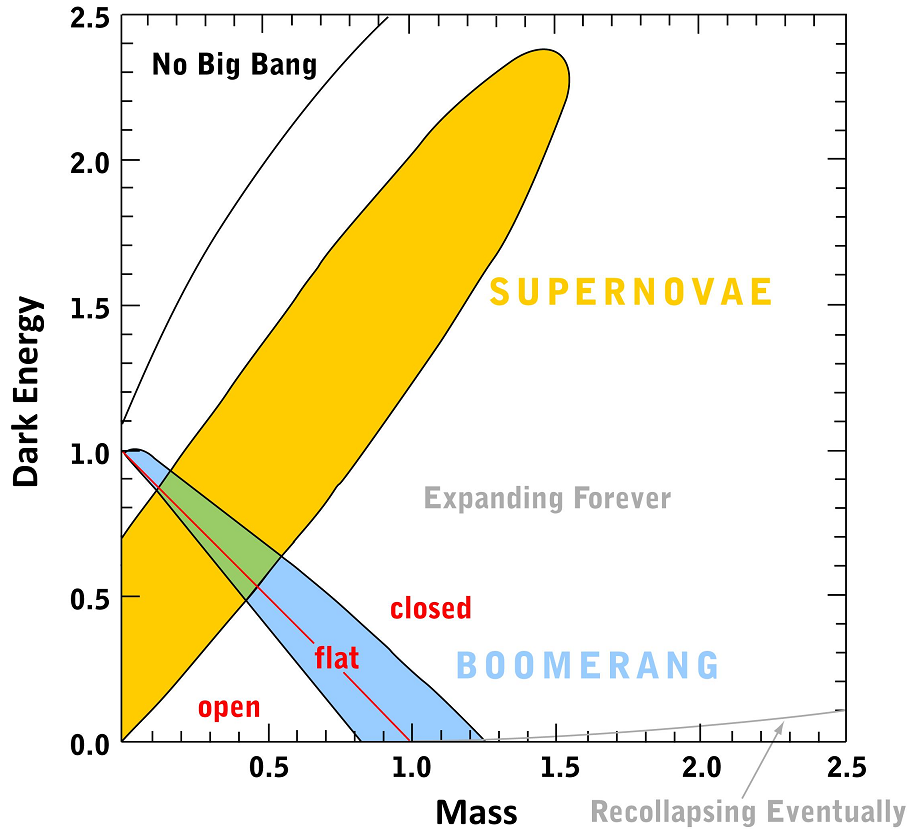

These supernova measurements provide information about the mass dark energy fractions, shown on the right. It doesn’t provide an exact answer for each, but instead gives an estimate, shown as the yellow oval to the right. This shows that the values for dark energy fraction and mass fraction fall somewhere inside that oval. Supernova data largely point towards the existence of dark energy, but not definitively. The oval is bisected by the red “flat universe” line, along which the true value would lie if there universe were shown to be flat. Thus, determining the shape of the universe is a key step towards determining the existence of dark energy.

Cosmic Microwave Background

The second experiment we’ll look at is the observation of the cosmic microwave background, which is the residual light left in the universe from the Big Bang. This corresponds to a temperature of 2.7 Kelvins (-455 °F), and gives a direct measure of the radiation fraction, which turns out to be the minute value of 0.01%. It also allows astronomers to determine the curvature of the universe.

The notion of curvature is difficult to visualize. Our linen sheet from earlier describes a flat universe. A closed universe would be a world contained along the surface of a spherical shell, and an open universe is a saddle-like shape.

The temperature of the cosmic microwave background is remarkably consistent, but small part-per-million fluctuations in it (called “anisotropies”) can be observed, which come from sound waves in the very early universe, just after the Big Bang. Astronomers know what pitch these sound waves should be, so by measuring the residual waves in the sky, they can tell whether or not the observed angle is from a flat or a curved universe. An experiment called BOOMERanG collected data in a balloon above Antarctica, and found that the Universe is flat, and so there is zero curvature. Going back to the graph earlier, the combination of supernova and BOOMERanG data puts the dark energy and mass fractions somewhere inside the green wedge. We’ll need one more experiment to precisely determine what the fractions are.

Baryon Acoustic Oscillations

Returning to the model mentioned at the beginning, we now have values for the radiation fraction and the curvature, and a relationship between the mass and the dark energy fractions. The final piece of our puzzle comes from baryon acoustic oscillations, which are the peaks and troughs in the concentrations of galaxies found in the universe. Essentially, the size of these oscillations gives a number for the mass fraction of the universe, which turns out to be roughly 30% of the universe. Now that we have the mass fraction, we can figure out the dark energy fraction directly.

Putting It All Together

Merging the three different experimental data sets, the true story of dark energy surfaces – a whopping 70% of the universe is made up of dark energy. Of the 30% that is mass, it turns out that only 4% is ordinary matter, the stuff we think of being in the universe (stars, planets, interstellar dust, etc.) while the other 26% is dark matter (different from dark energy).

So What?

There’s strong evidence that dark energy exists, and experiments based on different physics come together to support each other. In fact, dark energy comprises most of the universe. However, the nature of dark energy is still unknown – all our evidence is indirect (hence the moniker “dark”). Even though it makes up so much of the Universe, its tendency to “push back” means that it has a very low density (10-26 kg/m3). Theories about the nature of dark energy abound, but, until there is a way to experimentally challenge each, the true identity of dark energy will remain a mystery.

Dan is a physics Ph.D. student at University of Colorado Boulder and is a graduate research assistant at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. His research involves the development of infrared lasers for the detection of atmospheric greenhouse gases. You can reach him at daniel.maser AT colorado.edu.

Dan is a physics Ph.D. student at University of Colorado Boulder and is a graduate research assistant at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. His research involves the development of infrared lasers for the detection of atmospheric greenhouse gases. You can reach him at daniel.maser AT colorado.edu.

References / Further Reading

- A. G. Riess et al., Astronomical Journal 116, 1009 (1998).

- S. Perlmutter et al., Astrophysical Journal 517, 565 (1999).

- B. Schwarzschild, Physics Today 60, 21+ (2007).

- B. Schwartzschild, Physics Today 54, 17 (2001).

- P. J. E. Peebles and B. Ratra, Reviews of Modern Physics 75, 559 (2003).

- P. de Bernardis et al., Nature 404, 955 (2000).

- D. J. Eisenstein, New Astronomy Reviews 49, 360 (2005).

- S. Perlmutter, Physics Today 56, 53 (2003).

- J. B. Hartle, Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein’s General Relativity (Addison-Wesley, 2003).

- W. Hu, N. Sugiyama, and J. Silk, Nature 386, 37 (1997).

- L. Miao, L. Xiao-Dong, W. Shuang, and W. Yi, Communications in Theoretical Physics 56, 525 (2011).

- J. A. Frieman, M. S. Turner, and D. Huterer, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 46, 385 (2008).

- M. Kowalski et al., Astrophysical Journal 686, 749 (2008).

- J. E. Lidsey, Temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, (2003).

- Planck Collaboration, P. Ade et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics (2013), arXiv:1303.5076.

- Planck Collaboration, P. Ade et al., (2013), arXiv:1303.5075.

- H.-J. Seo and D. J. Eisenstein, The Astrophysical Journal 598, 720 (2003).

S. W. Allen, A. E. Evrard, and A. B. Mantz, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 49, 409 (2011).

Great primer on such an interesting (and frustrating) topic. We seem to know just enough about dark energy to know how little we really know about it. I hope to see a major breakthrough in my lifetime, which I feel will be remembered on par with great advances in astronomy like the cementing the heliocentric view of the solar system, but in the mean time I guess I’ll just have to settle for proudly wearing my “I find Dark Energy repulsive” t-shirt.

[…] Dark energy and the nature of the universe are two of the most exciting discoveries of the past couple decades, but can be some of the most difficult conce […]

[…] “Shedding Light on Dark Energy PLoS Blogs (blog) The second experiment we'll look at is the observation of the cosmic microwave background, which is the residual light left in the universe from the Big Bang.” […]

Dark energy has not been “discovered”. It was made up to explain which appears to be an accelerating expansion of the visible universe. Sometimes we need to say that “we don’t know” and not be quite so hasty to come up with an explanation which is completely scientifically unverified. There is a LOT more to the universe that we don’t know that we don’t know. This is all very Ptolemy-like indeed.

You are correct in that all our evidence for dark energy’s existence is indirect, but I would not go as far as saying that the explanation is hasty or completely scientifically unverified. Dark energy is by far the most widely accepted theory for the accelerating expansion of the universe, and the theories that incorporate dark energy have been verified by a number of other studies that rely on different physics from that involved in observing the expansion of the universe. I’ve touched on some of these but there are also several others (such as this). There are a number of alternative theories but dark energy in its current theoretical form is the predominant theory right now.