Ebola Immunopathology and the Outbreak in West Africa

Ebola virus (EBOV) is a highly virulent pathogen, resulting in death by Ebola hemorrhagic fever in up to 90% of people who contract the virus. There are no drugs to treat it, and no vaccines yet to prevent it.

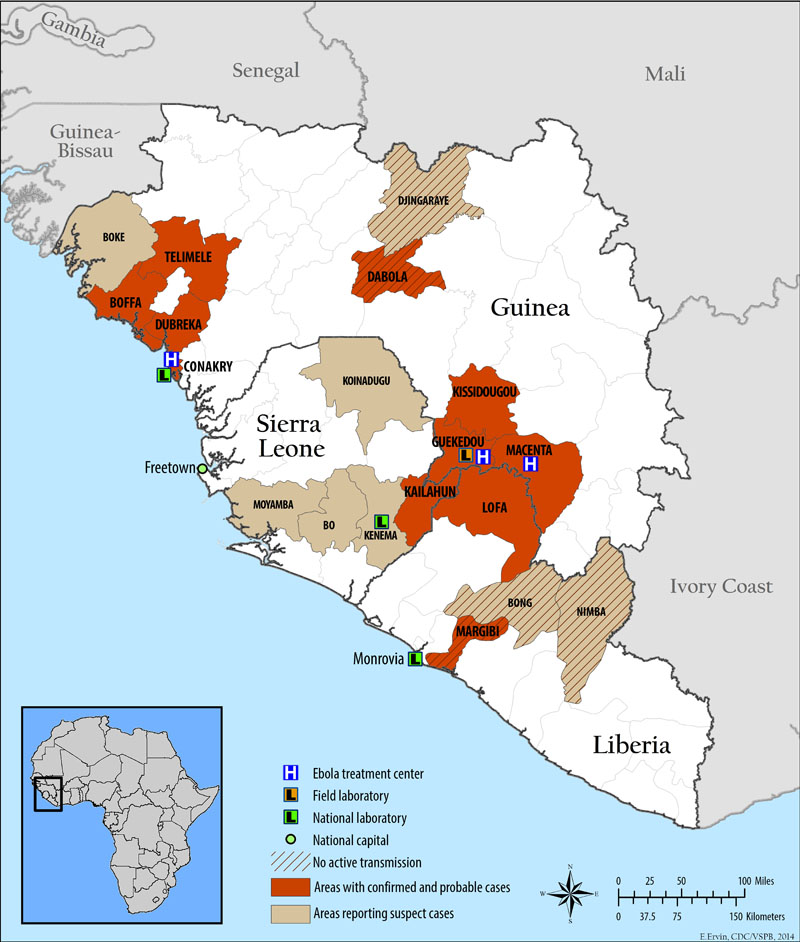

There is an Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and it has been ongoing for several months, since the first death occurred in December 2013. The most recent counts from the World Health Organization include 328 cases, with 208 deaths, in Guinea so far, with additional cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Between May 29 and June 1 alone, there were 37 new reported cases and 21 deaths.

By April, Médicins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), which has been the lead aid organization for the outbreak, was calling the epidemic ‘Unprecedented’. What makes this epidemic different, in addition to the fact that this is the first outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, is that cases are not geographically isolated. Cases have been occurring throughout Guinea, and now Sierra Leone and Liberia as well. Senegal even closed its borders to Guinea in April for fear of spread of the virus.

Ebola virus is carried by fruit bats, and is transmitted to and among humans and other primates by blood and bodily fluids at skin and mucosal surfaces. The most common routes of exposure for humans are handling infected bushmeat, contact with the remains of an individual who has succumbed to the virus, or occupational exposure to health workers by needle-stick.

The strain causing the present epidemic has been sequenced and characterized, and was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April. It represents the emergence of a new clade of the virus – unique, but related to Zaire ebolavirus, an extremely virulent strain that has caused epidemics in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gabon.

So what makes Ebola virus so deadly? And why do some individuals progress to Ebola hemorrhagic fever and death, whereas others recover?

Ebola Immunopathology

Ebola immunopathology is characterized by uncontrolled inflammatory responses by monocytes and macrophages in the early stage of infection, coupled with immune suppression and the destruction of several cell types including dendritic cells (DCs) and endothelial cells in the later stages of infection. This ultimately leads to the collapse of the vascular system, shock-like symptoms, uncontrollable hemorrhaging, and death.

Compared to those who recover from Ebola infection, victims exhibit high viral loads, an absence of cytotoxic CD8 T cell activation, below-normal numbers of T cells, and high nitric oxide production, a sign of macrophage activation. Furthermore, recovered individuals have detectable levels of anti-EBOV antibodies in the blood at the onset of symptoms, whereas susceptible individuals do not. Those who succumb to the virus mount a robust but ineffective innate inflammatory response, followed by a failure to induce adaptive immunity. Viral replication and cell death continue, unchecked.

How is it that the innate response is both strong and ineffective? This paradox can be explained by differential effects of ebola virus on macrophages and DCs. While strongly activating monocytes and macrophages, ebola-infected DCs are inhibited in activation and function.

Ebola activates monocytes and macrophages

Virus-activated monocytes and macrophages secrete an abundance of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines like tumor necrosis factor (TNFa), IL-1β, macrophage inflammatory protein-1a, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and large numbers of infected macrophages undergo activation and apoptosis. However, this is insufficient to deter viral spread. Macrophage apoptosis recruits more monocytes and neutrophils that further the inflammatory response and provide new host cells for the virus.

The unchecked production of pro-inflammatory mediators is cytotoxic to the surrounding tissue, and likely contributes to the hemorrhagic pathology of Ebola infection, by increasing vascular permeability. That is not to down-play the effects of the virus itself, which has a particular tropism for innate immune cells and endothelial cells, and induces cell lysis in most if not all cells it infects.

Ebola impairs and co-opts dendritic cell function

Dendritic cells (DCs) serve as the bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. When functioning normally against infection, DCs internalize a pathogen or a piece of it, and then process and present signatures of that pathogen to T cells in the lymph node. Dendritic cells also secrete activating cytokines like interferons (IFNs) and IL-12, and express co-stimulatory molecules to further induce responses from cells of the adaptive arm. Ebola virus, however, inhibits dendritic cell function by several mechanisms. Ebola-infected DCs fail to secrete IFNs and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, fail to upregulate costimulatory molecules, are impaired in antigen presentation and processing, demonstrate increased expression of inhibitory molecules, and are in all poor activators of T cells. These effects are dependent on the Ebola envelope glycoprotein.

A particularly interesting feature of Ebola, is that its sticky! The virus binds C type lectins on the surface of a number of cell types, including the lectin DC-SIGN which is highly expressed on dendritic cells. The benefit of this for viral pathogenesis is unclear, but may facilitate viral entry into DCs and other cells, or may simply allow the virus to hitch a ride through the lymphatic system and disseminate infection.

Outlook

The immune response to Ebola virus gets only half-way there in fatal cases. The innate immune system is alerted and activated, but then the virus inhibits the initiation of an adaptive response by DCs. The unchecked innate response only contributes to the vascular permeability and tissue damage that proves fatal. In short, there is a lot that we don’t know about Ebola immunopathology, but it is clear that those who recover are able to initiate a T cell response and the production of antibodies.

A vaccine for Ebola is still 5 years away or more, and is being actively pursued by researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and Thomas Jefferson University. BioCryst Pharmaceutical in Durham, NC is pursuing a drug candidate, and Mapp Biopharmaceutical in San Diego is currently developing a monoclonal antibody cocktail in partnership with the Public Health Agency of Canada.

None of the above leads will help in the present epidemic. The current strategy is to provide medical care to and observation of those infected, and attempt to contain the spread of the virus any further.

Rachel Cotton is a Senior Biological Sciences major in the Eck Institute for Global Health at the University of Notre Dame, where she conducts immunology and infectious disease research. She is Co-Editor in Chief of the undergraduate research journal, Scientia

[…] Ebola virus (EBOV) is a highly virulent pathogen, resulting in death by Ebola hemorrhagic fever in up to 90% of people who contract the virus. There are no vaccines yet to prevent it. […]

[…] Ebola virus (EBOV) is a highly virulent pathogen, resulting in death by Ebola hemorrhagic fever in up to 90% of people who contract the virus. There are no […]

[…] PLoS Blogs (blog) Ebola Immunopathology and the Outbreak in West Africa PLoS Blogs (blog) Ebola virus is carried by fruit bats, and is transmitted to and among humans and other primates by blood and bodily fluids at skin and mucosal surfaces. […]

I am going back to the chemical signaling system of the blood stream.

If you can Id the css that survivors have that the dead did not produce then maybe you could try and artificially produce it and inject into patients to see if it helps the mortality rate

Your blog is very interesting and informative.

Dendritic cell function impairment will be a major challenge in vaccine development.

In the absence of induction of memory B and T cells, effective vaccination is going to be difficult.

Any more evidence ( apart from the cited one) exists regarding DC impairment in Ebola.

Please share.

[…] https://blogs.plos.org/thestudentblog/2014/06/06/unprecedented-ebola-outbreak-west-africa/ […]

[…] 1. https://blogs.plos.org/thestudentblog/2014/06/06/unprecedented-ebola-outbreak-west-africa/ […]

You hear of Ebola but most people are not aware of what the virus is, how it is contracted and steps to take to protect yourself. You areticle spells all that out…Thanks for an interesting article.

[…] innate immune system. For a slightly more technical explanation of the same, Rachel Cotton posted a nice overview of Ebola’s immunopathology on PLoS Student Blog in June. And for something more detailed, here’s an extract and link to […]

I have read a few articles about Ebola but nothing as detailed as this. I sincerely thank you for the indept research.

Very informative thanks for sharing