On being ‘right’ in science

This post will be cross-posted on Berkeley Science Review

The other day I was standing around with a few friends arguing about ergonomics (these are the things you do when you’re a graduate scientist). At one point, my friend referenced a presentation that was chock full of the worst kinds of sensationalist science writing (it said that the act of sitting was literally killing you).

As a scientist and writer myself, I jumped all over the presentation, calling it sham science, and pointing out the many ways in which it was confusing or obscuring the truth. Expecting to be met with nodding approval, I instead faced several annoyed looks and the strong feeling that I was being wished out of the room. I didn’t understand what was wrong – they had presented a piece of evidence, and I had summarily shot it down. Isn’t that what arguing is all about? Instead of feeling right, I felt like a jerk.

And then I realized something: it didn’t matter whether I was right; nobody was listening to me anymore.

Many scientists run into this situation on a daily basis, but understanding this problem digs into one of the biggest crises facing scientific research today: there’s a difference between being right and being persuasive. The first entails having the facts straight, and the second means convincing someone else to believe them.

As an academic, I’ve often heard that “the facts speak for themselves”, or that one need only to “look at the data” in order to see the truth. Unfortunately, experience has taught me that neither of these statements is correct. Facts are always colored by the context in which they are presented, and data can be massaged and molded to tell almost any story you want. And so what if you’re correct, if nobody will pay attention to you in the first place?

This brings me to a saying that one of my advisors is fond of sharing with his students:

Never hesitate to sacrifice truth for understanding.

Let me take a second to tease this sentence apart. On its surface, it would seem that this is an almost heretical idea in the world of science—we’re all pursuing truth, not trying to hide it. However, as anyone who’s read an article full of confusing scientific jargon will tell you, incomprehensible truth is just that: incomprehensible.

As a scientist, our job is not only to make discoveries about the world, but also to share our experience and our findings with those around us. That’s where the persuasion comes in.

Let me give you two sentences, and you tell me which one is better:

- Neurons are composed of a lipid bilayer with embedded trans-membrane proteins for the purpose of transmitting ions across the cell membrane. Upon firing an action potential, electrical and chemical gradients cause an influx of sodium, causing a spike in membrane potential. Calcium channels open and an influx of calcium cleaves SNARE proteins, releasing vesicles containing neurotransmitters.

- Neurons are cells in the brain with tiny “channels” embedded on their outside. These channels allow electrically-charged chemicals (called “ions”) to go inside and out of the cell. When sodium ions enter the cell in large amounts, neurons will “fire” in an event called an action potential. This opens channels for calcium ions, which enter the cell and cause the release of packages of neurotransmitter.

They’re both correct, but unless you’re a neuroscientist the first one is considerably harder to read. If I were to give a random person the first explanation, they’d probably think: “well, that sounds smart but I have no idea what he’s talking about.” If I gave you the second, you’d have an intuition (albeit incomplete) for how a neuron operates. That’s sacrificing truth for understanding, and it’s essential as we attempt to make our science understandable by laypeople, politicians, businesses, and even other scientists.

So why belabor this point? Because scientists are taught to speak like explanation 1, even though the vast majority of people think in terms of explanation 2. We offload the incredibly important task of science communication to a vast army of journalists and hope that the few Carl Sagans and Neil deGrasse Tysons of the world will carry the load for us. No wonder there’s a disconnect between the scientific community and the rest of the public.

At this point, someone usually chimes in with the “science doesn’t need the input of ‘non-scientists’” argument, suggesting that we only need to talk amongst ourselves in developing new theories of the world. Sorry, I’m not buying that.

Consider the fact that scientific theory and uninformed hand waving are often presented as equal and opposing sides to an argument in the media. Clearly, we are not getting the message across to the public that science is not opinion, it is an argument grounded in facts. It’s incredibly important to think about how we phrase our understanding of the world, as well as how we can make our ideas more relevant, interesting, and clear to the public. Don’t believe me? Just ask the climate scientists.

As a young scientist, there is a lot of pressure to focus all of my efforts on my scientific peers, to keep up with the latest computational jargon, to remember the recently created acronyms. However, this will only make up part of my education in graduate school. The other part, equally as important as the first, entails sharing those ideas with others, using them to better the world, and inviting those around me to forge ahead into the unknown as we take the next scientific leap.

Chris studies cognitive and computational neuroscience, attempting to link higher-level theories of the mind with information processing in the brain. He’s also an avid science communicator – check out his posts on the Berkeley Science Review and follow him on Twitter at @choldgraf

I agree with your main points, but the quote, “Never hesitate to sacrifice truth for understanding”, makes me very uncomfortable and doesn’t actually represent your real message here. I believe that there is a way to communicate science in an accessible and accurate way, even down to the finer details such as what SNARE proteins are and how they work.

In particular, I would like to see a change in the way research articles are written, so that the content is accessible to anyone who reads them.

@ActiveScientist

You’re right – the quote makes a pretty sweeping statement for a very nuanced and difficult issue. I think a better version might be “Never hesitate to sacrifice truth for understanding, given that you’re not distorting reality and you’ve got good intentions”, but I didn’t want to put words in their mouth 🙂

I think you bring up an interesting point though – do you really think that all science communications could be made understandable to anyone who reads them (e.g., given publication length requirements)? It seems like it would be a really difficult challenge to satisfy everybody all at once. An alternative approach might be to have different versions of an article, all of which is approved/created by the author. Though again, it’d be hard to institutionalize and enforce.

I prefer the statement:

“You don’t truly understand something until you can explain it to your grandmother”

This is a really great piece to help people keep things in perspective. As a grad student myself, I often find myself struggling to explain what I do to the world outside of academia. Keeping in mind that simplicity doesn’t inherently mean something is worse, especially if your audience is new to the topic, is something a lot of us could benefit from. It also shows the importance of data visualization, as for me at least it’s been the best medium to convey your message to a wide ranging audience without sacrificing too much nuance.

The quote certainly stirred up a reaction in me and made me think, and that is always welcome!

I think it is possible to make all science communications understandable to anyone who reads them. Speaking as someone who has edited many reviews, clear communication is a rarity in research articles, but I have seen it done well. Good editors help (wouldn’t it be great if every institution had manuscript editors?). However, you bring up a good point.

Here is why my idea is not quite right: we don’t actually want to make everything from scratch, as your Carl Sagan quote reminds me. We don’t want to have to explain what an action potential is every time we write about neuroscience. That would be quite the giant manuscript. Perhaps a welcome consequence of having scientific articles online will be the use of hyperlinks embedded in the main text. The links could go to wikipedia, book chapters, etc that describe the basics for an unfamiliar reader. Then the article would only require a very general introductory paragraph with many hyperlinks to get people caught up if needed. This could even be separate from the main article, written for this purpose.

As for your idea of creating multiple versions of an article, I love it but don’t know many scientists who would/could spend time doing that. I think teaming up science communicators with scientists could be a solution, and this is happening more and more. If every lab (or at least every department) had a science communicator in training for this purpose that would be a good start. We talk a lot about how there aren’t enough academic jobs, so why not let the grad students interested in sci comm fulfill that role for their lab? Great practical experience that benefits all.

I will organize it, just give me the job!

@ActiveScientist

I would agree with that statement if it didn’t impugn the intelligence of my grandmother.

Nice article here Chris, scientists must be effective communicators above all else, otherwise we are nothing more than highly trained technical implements. The current political climate in this country renders the “science doesn’t need the input of non-scienctists” argument spurious, evidence of this can be clearly seen in the number of American scientist struggling to secure grants due to cutbacks in government funding.

Scientists pursue dazzling research demanding tremendous intellectual ingenuity yet often gauge success by the journal impact factor achieved at the end of a career. Scientists need non-scientists to fund all of this work, why then are we not reporting to the general public the incredible endeavors that we undertake? Instead we mystify our work in journals creating an information vacuum filled by climate change skeptics and anit-vaccine advocates. Taxpayers and foundation donors deserve a clear, understandable explanation of our scientific explorations if for no other reason than to provide them with a receipt for their expenditures, a tangible return on investment. As a community American science must become more adept at communicating why the collective body of work is vital to our national interest.

What if every published paper, in every journal concluded with a easily understood 300 word contextual synopsis penned by the reviewer/editor/publisher describing why the work was important to the scientific community at large, how prior research led to the current proposal and potential implications of the research relating to the telecommunications, medical, or agricultural industries, etc? Perhaps this could begin to provide some perspective to laypeople on how quality research begets quality research which culminates in real world applications and products like Blu-Ray discs, Viagra, MRIs and the internet. Also, classes in communicating science to the general public should be mandatory curriculum for graduate students; it is a mission critical skill if we hope to augment funding in the future.

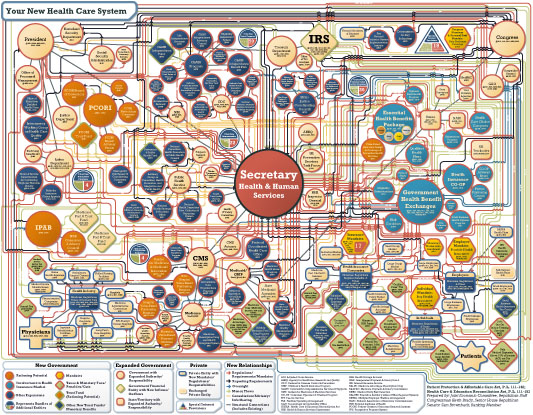

Yes, that’s quite a chart. When you consider who created it though–see “Prepared by: Joint Economic Committee, Republican Staff Congressman Kevin Brady, Senior House Republican Senator Sam Brownback, Ranking Member” in the lower right corner–and what their intentions probably are (casting the ACA as an intrusive “big government”), I think it makes the intended point quite clearly, actually!

Great post, and glad to see you guys up and running at The Student Blog! I think the bigger issue here is to know your audience. If you are talking to scientists, the language in Sentence 1 isn’t only encouraged, it’s appropriate. After all, if I’m a neuroscientist, that’s what I want to hear as that’s “my language.” But if I’m sitting around the dinner table with my family, then I need to use a different approach. At which point Sentence 2, using metaphors and similes to describe those concepts, is much more appropriate.

I would suggest that within each of those two domains you would then apply the adage of “Never hesitate to sacrifice truth for understanding.” Even when I’m speaking to a group of epidemiologists (my equivalent of neuroscientists), I’ll use the simplest, but most accurate language that I can that my audience will understand, and the same applies for those outside your field.

Great post!

‘————–

I prefer the statement:

“You don’t truly understand something until you can explain it to your grandmother”

————–

I’m not a fan of this. My grandmother worked on the first computer systems. She could explain a thing or two to you and me.

Certainly there needs to be a change in the way science is communicated in peer-reviewed journals. I have little difficulty understanding the articles in my own field, but it’s a different story if I wish to research a particular topic outside my field, and thus comfort zone. I’m not so convinced the hyperlink idea would work. It could lead to unintended distraction. In my own experience I’ve found that I’ve ended up looking up explanations of the technical jargon through sites like wikipedia, and end up becoming so lost in trying to understand each new piece of jargon that I either lose interest in reading the original article or I forget what the original article was entirely! I don’t think we should do away with the technical jargon though either, it has it’s place and is relevant to those in the field it applies. I think a good solution would be to have as perhaps an alternative abstract, something along the lines of an accompanying press release, written by the author(s), in laymans terms which outlines the research, methods, discussion/key points and conclusions of the article. This would lay the introductory foundations for the reader to, if they wish to, build upon their understanding by reading the actual article afterwards.

I would say rather than sacrificing truth, it is more like sacrificing complete accuracy to give the big picture view. To give an example, the big picture of physics is taught in middle school and high school, and only in college courses and above would the details and mathematics behind the theories be explained.

[…] just into arguing with other people on the Internet about science — you need to read this post by neuroscientist Chris Holdgraf. It’s a great explanation of why “the data speaks for itself” isn’t a […]

Does science need to be ergonomically designed?

As the dictionary puts it: “minimizing operator fatigue and discomfort”.

I love the idea of using hyperlinks more in science communication. I’d go one step further: why don’t research articles themselves do that? Authors could be given the option add links from any jargon or complicated concepts to introductory level explanations elsewhere on the web. There could even be a “show/hide links” option if researchers want to read the article without seeing the links. For a place like PLoS, with articles open to the public, it could be a great way to convince the non-scientist that they can, in fact, dig into the scientific literature and learn something.

Stay tuned to The Student Blog – the post Friday will be addressing this very issue!

I asked my mentor teachers and professors this same question during my student teaching. To what extent should we stick to the capital T Truth if it seems to be getting in the way of student understanding? Or: how useful is metaphor as a teaching tool if it sacrifices accuracy in the process? A few of my teachers were a bit defensive about the idea, but jargon is alienating, and fewer disciplines are more jargony than science. Except maybe sailing.

I like to close out my discussions with students with a little clause, “It’s kind of like this… Not exactly this, but close.” I think as a science communicator, it is important to let people know when you are taking shortcuts, and hope that they decide to follow up on the ideas later, or hide them away to make other connections.

All right, but now I want to hear more about the presentation mentioned in the first paragraph. If you’re preaching the virtues of indolence, you’ve got a mountain of literature to overcome. There’s being obnoxious, and there’s being obnoxious and wrong as well.

Chris, this is a great article, and unfortunately, I too have encountered the same kinds of feelings when presenting ideas or trying to refute claims made by others…and this feeling of being a jerk when shooting down an argument isn’t contained by the boundaries of the natural and physical sciences. As a political scientist and economist with a business helping companies make better decisions, the barriers between massaging truth for understanding is no less acute, and it sometimes a painful sacrifice.

It seems to me that

Never hesitate to sacrifice precision for understanding.

qualifies as both truer and more understandable.

It also more directly echoes a related commandment regarding precision and accuracy.

He makes a great point. He sort of skimmed over the issue of persuasiveness taking the place of accuracy to the point where the reader has an oversimplified understanding of the subject. This can exacerbate and lead to a seriously skewed perception of the subject by the masses. This eventually generates a damaging resistance to further research and progress. Religious fundamentalist spreading lies about stem cell research is an extreme example of this. Yes it is important to write in a way that paints a clear picture for the reader, but accuracy should not be sacrificed without explaining the subject completely. Combining persuasiveness with accuracy would be the best way to approach this issue.

Good article, but I agree with other comments about “truth.”

Better to say “sacrifice technical details for understanding.”

Throwing “truth” under the bus is way too culturally and intellectually loaded to maintain the point you’re making.

[…] just into arguing with other people on the Internet about science — you need to read this post by neuroscientist Chris Holdgraf. It’s a great explanation of why “the data speaks for itself” isn’t a […]

Global Warming skeptics have also found that presenting data that falsifies the central theory of climate alarm which is that the old school greenhouse effect is suddenly assumed to be highly (3X) amplified by water vapor feedback. We can’t even get the message out to any Democrats so far that we even have a valid and rational argument, since we are continuously compared to moon landing deniers or the Flat Earth Society. So…I made some pretty infographics which did help convert Republicans to our side but so far most liberals are quite immune to them. Thus we are left with a waiting game, as temperature trends continue to refuse to notice “carbon pollution” and the trillion dollars that would have paid off all of your generation’s student loans has gone to Enron spinoffs like Solyandra. Suckers!

-=NikFromNYC=-, Ph.D. in carbon chemistry (Columbia/Harvard)

http://s24.postimg.org/498mmzb6d/2agnous.gif

http://oi56.tinypic.com/2reh021.jpg

http://s22.postimg.org/ulr1dg7jl/Sea_Level_Two.jpg

http://s23.postimg.org/47l8f5jvf/Tide_Gauges_Eye_Candy.gif

http://a2.img.mobypicture.com/8e1234d649766adfef528feb438395b9_large.jpg

http://oi54.tinypic.com/es5gev.jpg

[…] On being ‘right’ in science | The Student Blog […]

I think “sacrifice truth” is a clear overstatement. What you sacrificed in your example was detail, not truth. At least as far as I can tell the simplified statement does not make any claims the original doesn’t also make.

I think the key to good scientific arguing is in being able to strip away as much detail as possible without damaging the core statement. Without sacrificing truth, because if you actually did that, someone could call you out on it, and the reputation gained from that will only make it harder in the future.

… this is actually much much harder to do in real life (or even in a spontaneous discussion) than is seems. I know that feeling all too well: Having all the arguments but being unable to get people to think about (or even listen to) them.

I forwarded this to a science prof friend of mine.

I agree with Ann. This is a well-known issue in software development; we often struggle with finding the right level of abstraction both in our designs and in our communication. Even though abstractions are necessarily inaccurate to some degree, they are tremendously useful. They allow people to learn at the level of detail they are interested in, without becoming overwhelmed, and they allow engineers to manipulate ideas and designs at the level of detail that is most useful to them, without getting bogged down by irrelevant and unnecessary details.

I am not a scientist I am an artist, but I have Asperger’s Syndrome and I find the second one hard to understand and the first one is easy. All the detail is there and all the dots are connected and accounted for. the second one sounds like it was rearraged to accomodate NT thinking, and it’s more confusing because it’s vague. you don’t see any of the “why’s” all you see is the “what’s”. I guess with the second explanation it accomodates people who cannot hold enough information in their heads all at once, so they need things taught in layers instead of giving it all at once. It would feel like a cognitive jump they aren’t ready to make. I realize that scientists are NT people too and not Aspies, so reading the first one, for me it seems to make sense to put all the detail in and that is the way I grasp it, but I can bet that it takes a scientist years to put all that information together. No, writing that is more difficult would be technical books at a university level, because those are filled with acronyms that people don’t know.

The reason why people don’t like you when they shoot their arguments down is because, there is actually an study done on thinking, and even the highest logicians (that don’t have Asperger’s Syndrome) do this: the brain first has a gut feeling, THEN it sets out to prove the gut with the brain. So I would expect that people’s guts are all feeling the same thing, and the proof being laid out agrees with their gut, so in effect, when you cut down their logic, you are indirectly attacking them emotionally.

This reminds me of Feyerabend’s work on linguistics in scientific exposition. While specific language is called for in in ever more specific scientific fields, there is also a creeping sense of elitism in scientific discourse that makes it inaccessible to the public. Public education MUST go hand-in-hand with scientific discovery. Simply publishing a paper is no longer enough.

A lot of folks have taken issue with the concept of sacrificing truth. I’d like to take issue with the claim that science is based on facts. The author wrote:

“science is not opinion, it is an argument grounded in facts”

But this is not true at all. Science is an argument grounded in evidence. Evidence comes from observation. Observations are always biased, sometimes fatally so. Theoretically science gets around bias by repeating experiments. In practice, the scientific community has so spectaculary failed to control for bias that in some fields one *should* be very suspicious of “scientific” claims.

IMO, the recent history of big public failures of peer-reviewed science – many of them involving pharmaceutical companies with huge financial conflicts of interest and regulators/legislators that are owned by weathly lobbyists – has made all of science look unreliable, and given “deniers” of every stripe reason enough to ignore evidence even when it’s persuasive.

The culture of science needs to change if scientists want the public to trust their results. This starts, but doesn’t end, with open-access publishing, and sharing of all data involved in trials.

[…] you can explain it to your grandma.” Whether or not these words were actually Einstein’s, they’ve been used again and again to encourage students to explain highly technical details in a simple way so that […]

[…] know you are right but no one is agreeing with you. When we wrote about myside bias last week, the article stimulating today’s post had not yet been […]

Just use appropriate synonyms that are in common use outside of the narrow scientific field you’re in, instead of the jargon you’re used to, and leave out some less critical detail unless someone asks more in-depth questions, showing that they want to know more. You’re communicating a model, a simplified version of events, to the average person.

[…] • Can Ireland’s Celtic Tiger roar again? (Washington Post) • On being ‘right’ in science (Plos) • The Mystery of Cheap Lobster (Atlantic) • Alvy Ray Smith: RGBA, the birth of compositing […]

[…] • Can Ireland’s Celtic Tiger roar again? (Washington Post) • On being ‘right’ in science (Plos) • The Mystery of Cheap Lobster (Atlantic) • Alvy Ray Smith: RGBA, the birth of compositing […]

[…] Holdgraf, PLOS.org, On being ‘right’ in science, here. The distortion […]

[…] being ‘right’ in science” https://blogs.plos.org/thestudentblog/… by choldgraf via […]

The best scientists do their best to try to stick to facts. Scientists are human beings so they don’t always succeed. But critics are also human and their critiques reflect biases and self-interest as well.

As for the Big Pharma, the results of their studies are trade secrets and are therefore legally protected from public scrutiny. What they do release is carefully redacted and can in no way be described as “peer-reviewed.”

Scientific complexity is unavoidable. If I remember correctly, in Gleick’s bio of Richard Feynman, a reporter asks him to explain in simple words why his research earned him a Nobel Prize, to which Feynman replies something like ‘If I could explain my findings in simple terms I wouldn’t deserve a Nobel Prize!’

Being right or persuasive is politics and not science at all. Science is a process and consists of the rule of reproduce-ability by an arbitrary human. All else is narrative fed by agenda politics to maintain the balance of existing payrolls. Truth is reproduce-able or it’s not and the absolute defense against the libel of existing ignorance. Relax and be seeing that nature does not know how to lie and most humans grow to buy a conveniently placed lie rather than think for themselves and decode nature.

[…] On being ‘right’ in science (Plos) […]

[…] On being ‘right’ in science (Plos) […]

[…] On being ‘right’ in science | The Student Blog. […]