Digesting The Past

This article is being cross-listed on The Berkeley Science Review. Check out some other really interesting pieces there!

A few weeks ago, I was having coffee with a friend from the Hopkins molecular biology program; he left me somewhat dumbfounded with the story he told me. It involved a walking, talking experiment and an obsessed scientist (which one isn’t?) who revolutionized the concept of what makes humans…well, human; that is, it shifted the idea that the stomach contained the contents of humanity to the brain. This story is also inspired by my recent completion of a neuroscience boot camp at UC Berkeley. So without further adieu, here is the serendipitous and lucky story of Alexis St. Martin: the man with a hole in his stomach and his surgeon, William Beaumont.

On June 6, 1822 in Mackinac Island, Michigan, a French-Canadian fur trader, Alexis St Martin, was shot in the stomach when a shotgun was accidentally discharged (Fig 1). Luckily for Alexis, the fort’s doctor, William Beaumont, was nearby and quickly began to treat him. As if the damaging impact of a shotgun blast wasn’t enough, Beaumont’s treatment was unsterile and anesthetic-free. Mind you, this all happened before Louis Pasteur came up with his famous germ theory of disease. At the time it was generally accepted that God and miasmas caused plague and disease: people would resort to praying and burning tar to ‘cleanse the air’ of disease. I’m therefore sure Alexis relived the pain of his shotgun blast several times during his surgeries with Dr. Beaumont.

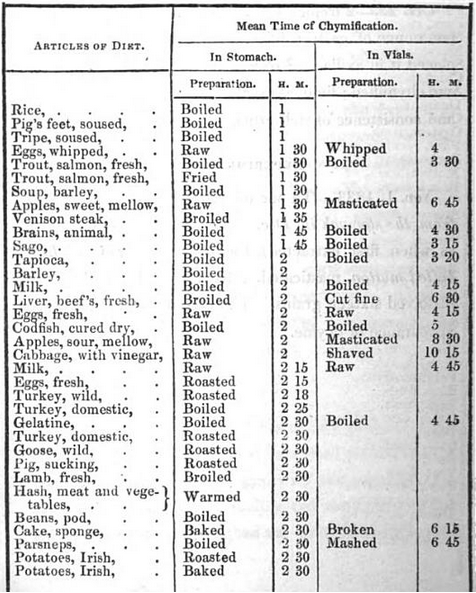

Alexis had several wounds from the blast, but the most significant of all was a gaping hole that never fully sealed, which formed a fistula. Nonetheless, he lived, remarkably. And since Alexis was unable to work due to his circumstances, Beaumont hired him as a handyman. This gave Beaumont a fantastic opportunity, one he exploited to a great degree, once he realized what he had in front of him during one of their wound cleaning sessions. That is, a peek (literally) into human digestion: a process people had known little to nothing about prior to Beaumont’s reportings. Before long, Beaumont began performing experiments on Alexis (Fig 2). These involved dipping food into the fistula and measuring the amount of time it took to digest. Vegetables and chunks of meat were tied to a string and inserted into Alexis’ stomach. Beaumont made him fast for hours on end, then removed gastric juice from his stomach and watched it digest foods in vials. Things like corned beef took almost 5 times as long outside the stomach than inside to digest—neat, huh?

I highly recommend checking out “Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion.” by William Beaumont, M.D. It’s free and if you skip to page 117 you’ll see Beaumont’s experimental documentation. As an example, I included experiment 68 below:

“Experiment 68.

At 9 o’clock P.M. same day, St Martin having eaten nothing since 2 o’clock, and feeling quite hungry, I put into the stomach, at the aperture, eight ounces of beef and barley soup, introduced gently through a tube with a syringe, lukewarm.”

The medical profession benefited greatly from Beaumont’s myriad experiments. His findings forged a path for modern physiology based on observation and deductive reasoning. Soon after, other investigators, including Pavlov, began making fistulas—through less explosive means—on animals to better understand digestion and mammalian physiology in general. All in all, Beaumont reshaped the concept of what makes humans…well, human. Initially people thought the stomach contained the essence of humanity, but Beaumont disproved that dogma by decomposing food, chemically, outside the human body. This realization caused people to think more deeply about what it means to be human.

Alex Padron is a first year graduate student in the UC Berkeley Molecular and Cell Biology program. He is interested in science and in empowering the general audience by making science make sense. You can follow him on Twitter @apadr007 and Google+ gplus.to/apadr007

[…] article is being cross-listed on the PLOS Student Blog. Check out some other really interesting pieces […]

[…] article is being cross-listed on the PLOS Student Blog. Check out some other really interesting pieces […]