Waving the red flag: The search for early markers of Alzheimer’s Disease

“How can a three-pound mass of jelly that you can hold in your palm imagine angels, contemplate the meaning of infinity, and even question its own place in the cosmos?”

This eloquent quote by V.S. Ramachandran expresses the feelings of many of the people around the world who are celebrated Brain Awareness Week (#BAW2016), which occurs annually in March. This global campaign strives to inform the public about the marvels science has discovered about the brain and the benefits this research holds for all of us. Alongside enlightening discoveries about how the brain shapes our understanding of the world, researchers use various methods to improve diagnostics, and locate the causes and develop cures to brain diseases.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disorder characterised by its notable memory impairment, has become a beacon for brain research. The need for more research is further evident, as patient numbers are set to increase from 44 million people living with AD today to 135.5 million people worldwide afflicted by 2050. The growing global burden of AD will lead to significant economic and social costs, and governments all over the world – such as the UK, USA and Australia – have pledged more funding for research in an effort to fight the disease. Identifying early diagnostic markers is pivotal in AD research. Indicators that can allow for early diagnosis of AD is important for two key reasons: (1) to allow individuals and their family valuable time to accept the diagnosis and adapt their lives accordingly and (2) to understand the factors contributing to disease progression. By identifying early diagnostic markers, researchers are exploring the neural systems affected in the early stages of AD, and informing treatments and interventions that could slow down or modify the course of the disease.

How do we investigate risk of Alzheimer’s Disease?

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is viewed as a pre-dementia stage for AD and other dementias, and has improved our understanding of AD progression. MCI refers to a noticeable change in an individual’s cognition in one or more domains, such as memory or the ability to pay attention, but functional abilities preserved – such as the ability to pay bills, shop or prepare a meal. These individuals are able to remain independent and are not diagnosed with dementia. MCI could provide an insight into the aetiology of AD and flag risk factors for the progression of dementia and transition to the disease. Researchers are exploring various avenues concerning early diagnostic markers – from investigating the neuropsychological changes to searching for structural brain changes across time.

A recent study in PLOS ONE tested a multivariate prognostic model to predict the transition from MCI to AD using baseline data of 289 MCI subjects collected for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. These patients were placed in two groups, those who progressed to a diagnosis of probable AD within 36 months (p-MCI) and those who did not (n-MCI). The researchers chose to include data that would be routinely collected during a clinical assessment of dementia, such as brain scans from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cognitive and functional assessments, and blood samples. These resources provided more than 750 variables for the multivariate prognostic model. A thorough cross-validation framework was applied to assess predictive utility. The researchers used a method called Multiple Kernel Learning, which uses algorithms to integrate data from different sources and derive similarities between them based on their features. In short, this marked out which variables were best able predict progression from MCI to AD.

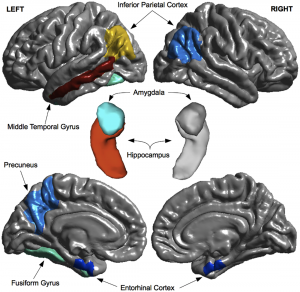

The results suggested that assessments of cognition and functionality were the best predictors for disease progression, with the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, Functional Activities Questionnaire and Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task best predicting the transition from MCI to AD. The p-MCI group demonstrated more cognitive deficits in these assessments than the n-MCI group at baseline. The hippocampal, inferior parietal and middle temporal regions of the brain also showed reduced volume in the p-MCI group at baseline in comparison to the n-MCI group – this also acted as a predictor for progression to AD. These areas are involved in memory, interpretation of sensory input and language abilities. Blood-based plasma proteomic data was the least predictive marker, failing to accurately distinguish between the two groups. The variety of neuropsychological tasks and brain areas as predictors suggests that subtle impairments in cognitive domains, aside from memory, may be a risk factor for AD. This study provided evidence of the predictive properties of routine clinical tests for AD, a beneficial approach, as these resources are easily accessible and cost effective.

Why is identifying diagnostic markers for Alzheimer’s Disease important?

While MCI can be an early indicator of Alzheimer’s disease, it can also develop into other forms of dementia or in some cases, remain stable. Misdiagnosis between the dementia subtypes is common, particularly between dementia with Lewy bodies and AD – with rates of misdiagnosis as high as 83% reported. This can have a severe impact on patients’ lives as accurate diagnosis is essential for appropriate treatments and interventions. Early diagnostic markers could strengthen the diagnosis of AD and improve management and treatment of the disease.

While the idea of finding early diagnostic markers for AD seems a relatively simple suggestion, it is complicated. The models developed to predict the progression from MCI to dementia can only be as accurate as the clinical diagnosis of the disease. Because the clinical and pathological presentation of AD is notably heterogeneous, currently the only definitive way to ascertain the diagnosis is through post-mortem investigation of changes in the patients’ brain. The study described earlier fails to follow patients up to this stage and also ignores a range of other possible diagnostic markers, such as cerebrovascular fluid. While the study makes positive steps towards a more robust method for assessing risk factors for AD, more research is necessary, including replication studies and comparisons with other forms of dementia could benefit these findings.

One of the core things emphasized during Brain Awareness Week is the importance and necessity of brain research. Through research in dementia and the variety of markers that predict risk of the disease, scientists are conducting research to benefit our health and longevity.

References

Albert, M. S., DeKosky, S. T., Dickson, D., Dubois, B., Feldman, H. H., Fox, N. C., … & Snyder, P. J. (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia, 7(3), 270-279.

Kenigsberg, P. A., Aquino, J. P., Bérard, A., Gzil, F., Andrieu, S., Banerjee, S., … & Platel, H. (2015). Dementia beyond 2025: Knowledge and uncertainties. Dementia, 1471301215574785.

Korolev, I. O., Symonds, L. L., Bozoki, A. C., & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2016). Predicting Progression from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Dementia Using Clinical, MRI, and Plasma Biomarkers via Probabilistic Pattern Classification. PloS one,11(2), e0138866.

on Aging, T. N. I., on Diagnostic, R. I. W. G., Braak, H., Coleman, P., Dickson, D., Duyckaerts, C., … & Hyman, B. (1997). Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.Neurobiology of aging, 18(4), S1-S2.

Ramachandran, V. S. (2012). The tell-tale brain: A neuroscientist’s quest for what makes us human. WW Norton & Company.

Riverol, M., & López, O. L. (2011). Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease.Front Neurol, 2, 46.

Tiraboschi, P., Salmon, D. P., Hansen, L. A., Hofstetter, R. C., Thal, L. J., & Corey-Bloom, J. (2006). What best differentiates Lewy body from Alzheimer’s disease in early-stage dementia?. Brain, 129(3), 729-735

Vradenburg, G. (2015). A pivotal moment in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: how global unity of purpose and action can beat the disease by 2025. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 15(1), 73-82.

[…] Source: Waving the red flag: The search for early markers of Alzheimer’s Disease […]