The Art of Selling Science: Presenting an engaging scientific talk

The late great Shakespeare famously wrote in As You Like It, “All the world’s a stage,” and if that’s true, then oral presentations are an opportunity for your best performance. Presenting science is an art, and must be cultivated through practice, over time. The Genetics Department at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) recently hosted their annual retreat where students and faculty are invited to give oral and poster presentations. This made me consider which distinguishing features engage an audience and pull in the listener.

There are many, MANY resources, perhaps on your own campus or online, that offer advice on giving presentations. Here I will focus on some tips I’ve picked up from speakers on the delivery of a scientific presentation.

Be yourself – Often, when we see an engaging speaker, we assume they are naturally charming and engaging. That may be true, but not all of us are naturally charismatic, and that’s okay. By breaking down the tendencies of those speakers, we may find that they’re not so hard to develop over time. Start by isolating individual mannerisms to improve. For example, first focus on maintaining eye contact. Practice your talk focusing only on good eye contact with the audience. Once you’ve mastered that, work in other non-verbal communication, like smiling, or your tone and word dynamics in describing your data. Be enthusiastic when you get to the slide with your most exciting data. Try overacting first then tone down. Practice by yourself as many times as you need. Engaged audience members will respond when your excitement shines through your presentation.

Practice until you’re bored with it – I’m sure you’ve been to a great talk where the person was engaging, used some tasteful humor to start the talk, and the results and conclusions were crystal clear. They didn’t accomplish that feat by pure wit and charm. They practiced. Across any field, even the best and most engaging speakers practice giving speeches. Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, describes meeting preparations in her book, Lean In. She explains that being prepared when attending a meeting is not impressive – it’s required for maximizing the value of the meeting. Preparedness can lead to opportunities to collaborate or exciting job opportunities. Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson coined the term “deliberate practice,” defined as the, “repetitive performance of intended cognitive or psychometry skills–rigorous skills assessment.” Essentially, this means you are purposefully isolating and practicing a skill you wish to improve on, while getting immediate feedback to help you improve. Bottom line: practice with purpose.

Know your goals and know your audience – The goal of a presentation is not simply to get through it. You want to stimulate a thoughtful and engaging discussion of your work to better your hypotheses, foster new collaborations, and inspire ideas for the discussion section of your future manuscript. You know who your audience will be, so ask yourself what does your audience know? Tailor your presentation to your audience so that they can easily follow your story. You may come up with a different presentation for a group of geneticists vs. a group of bioinformatics vs. general public presentations. Your audience will appreciate your effort if you take the time to consider what you’d like them to get out of your talk.

I spoke with a fellow graduate student at BCM, Ninad Oak, (@NinadOak) whom I consider to be an engaged audience member. He offered his take from the perspective of the audience:

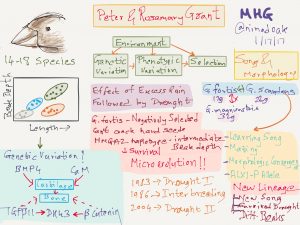

“Speakers who use schematics to explain findings and outline the bigger picture make it easier to follow the talk. As a student, I always felt it necessary to take notes at hour-long seminars. This helped me with following the talk and with future references. But I quickly realized that I missed out on a lot of data and it took longer to recollect the central theme. So I started sketching out picture summaries where I could include the central hypothesis of the talk along with re-drawing a couple of important results.”

These summaries are an excellent example of what you would like an audience member to take away from your talk, especially if they are not directly working in that field. It may be useful to draw a summary of your own talk to get an idea of which sections need special attention for clarity.

Don’t hesitate – I was told once by a PI, “Convince yourself, convince your PI, convince the world.” I liked the quote because following the mantra requires you to be confident in your work. Being confident in what you’ve done is critical, and if you’re not, you may consider testing additional hypothesis or explain the preliminary data to your audience and look for some crowdsourcing opportunities. Asking the audience for recommendations on a piece of data is a useful way to keep people engaged in a complex problem. In fact, they may have some insight from another field to offer you alternative perspectives. Be comfortable that you can’t possibly know everything and that you’re not expected to do so.

Don’t embellish – Audience members at talks are often more impressed by humility rather than stretching your findings to fit a hypothesis. Don’t be salesmanlike to convince others of your work. As explained by Peter Fiske, “selling your science” means highlighting your major findings and exciting data to help people focus on the most important aspects of the story. Effective data-highlighting will make the talk more meaningful for the audience and help them to follow your train of thought. You can practice data-highlighting by picking out your most convincing data, and practice using simple, unassuming explanations. Try explaining it several ways and find the one that really sells your point. This is the experiment you REALLY want them to understand, if nothing else. Be proud of your data and let it speak for itself just before you tell the audience what your conclusion is.

It would be impossible to include everything to make a great presentation in just one blog post. The goal of this post is to help you on the DELIVERY of your presentation. Don’t forget to spend just as much effort on the structure of your talk, your presentation visuals (powerpoint etc), and generating the data itself! I’ve included some useful links below that delve further into these presentation topics:

Helpful Links for more info:

http://blogs.nature.com/naturejobs/2017/01/11/scientific-presentations-a-cheat-sheet/

http://www.principiae.be/X0300.php

(great resource for host of presentation advice)

http://www.thinkoutsidetheslide.com/ten-secrets-for-using-powerpoint-effectively/

http://blogs.nature.com/naturejobs/2017/01/11/scientific-presentations-a-cheat-sheet/

References:

Sheryl Sandberg. Lean In. Knopf. 2013.

The Making of an Expert, K. Anders Ericsson, Michael J. Prietula, Edward T. Cokely, https://hbr.org/2007/07/the-making-of-an-expert, 2007.

Selling for Scientists, Peter Fiske, March 2014, http://blogs.nature.com/naturejobs/2014/03/21/selling-for-scientists/.

Ninad Oak on Twitter: https://twitter.com/ninadoak

Featured image by photographer Dirk Ingo Franke, depicting Frank Schulenburg during his presentation Taking Wikipedia in higher education to the next level, Wikimania 2011 in Haifa, Israel (August 4, 2011) CC BY-SA 3.0

[…] Source: The Art of Selling Science: Presenting an engaging scientific talk […]

[…] The Art Of Selling Science – Caitlin Grzeskowiak […]